Cellular-to-Satellite Connectivity is Coming From Apple, T-Mobile, and Others. Everyone Is Doing it Differently.

It may be an understatement to say that Apple has outside influence over the entire smartphone sector. Ahead of its anticipated launch of satellite messaging capabilities in the iPhone 14 we got cellular-satellite announcements from T-Mobile/Starlink, Huawei, and more. That’s not all; Verizon has been working with Amazon’s satellite group, Lynk Mobile just got a license from the FCC to start a space-based cell network, and Qualcomm is working on… something. This report covers Apple and T-Mobile in detail, with overviews of some of the other options.

Apple Emergency SOS via Satellite

Let’s start with Apple, because its solution – while limited in function – will have the most immediate impact. Apple sells over a hundred million iPhones annually. Along with Apple’s other safety initiatives in the iPhone 14 and Apple Watch, Emergency SOS via Satellite will save lives. All new iPhone 14 models will be able to reach emergency services even in areas where there is no cellular coverage whatsoever. The iPhone 14 goes on sale this week, and Emergency SOS via Satellite will go live in the U.S. and Canada in November, with other geographies being rolled out “in the months ahead.” Globalstar has satellites in orbit today with global coverage; the staggered launch appears to be largely due to the need to set up human-staffed centers in each country to relay the compressed text messages verbally to local emergency services.

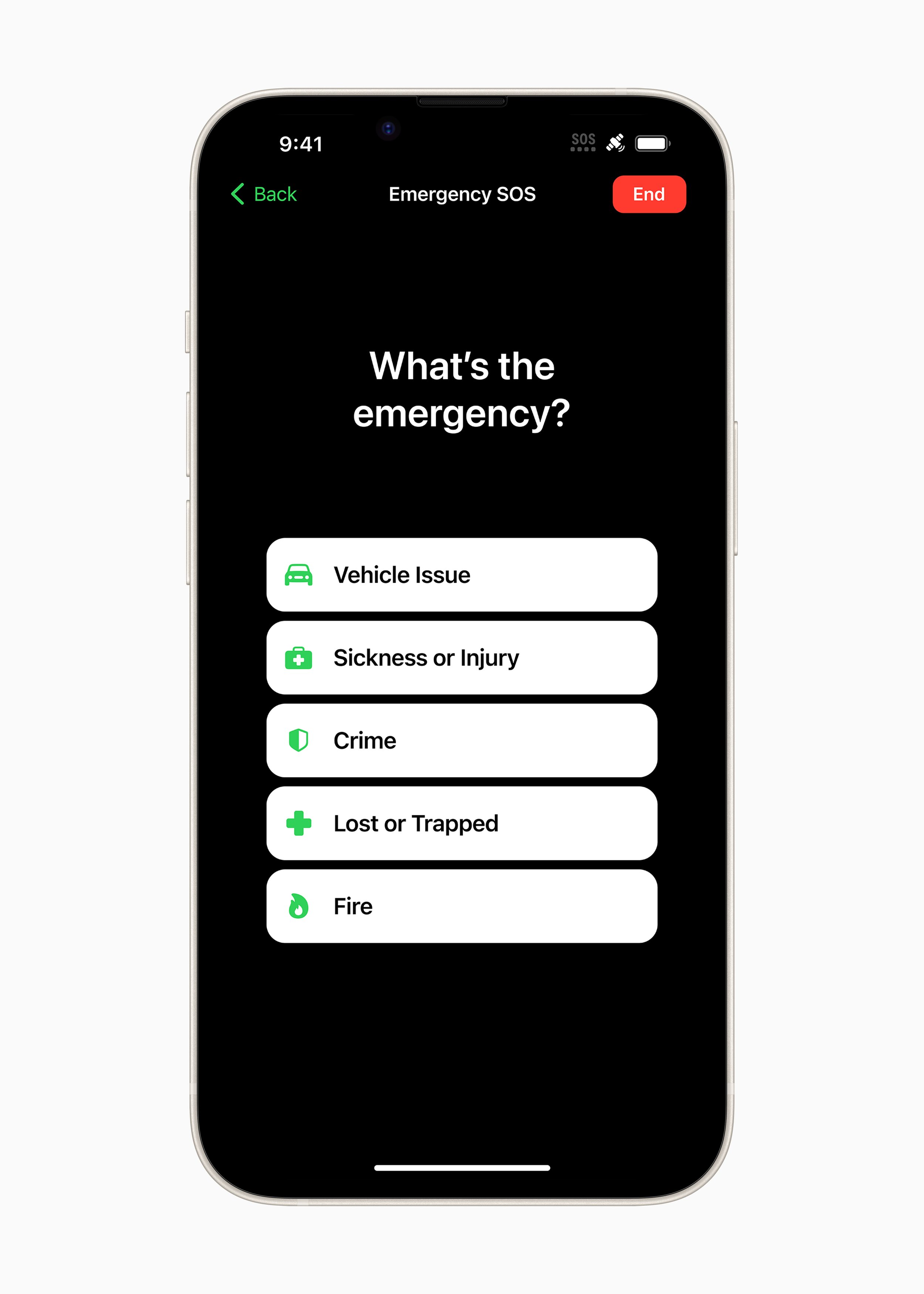

Apple is very deliberately branding this service as “Emergency SOS via Satellite.” While there will be a provision to send your location to loved ones, Emergency SOS via Satellite is otherwise designed solely to let you reach emergency services, not make phone calls or send general messages. The system works using a hidden app within the dialer and iMessages. If a user tries to dial 911 (or equivalent local number) and their local carrier does not have cellular coverage in the area but a different carrier does, the call will go out on whatever network is available. However, if there is no cellular coverage at all, then a dialog box will prompt the user through the most common emergency requests. The app then graphically directs the user to point the phone towards the position in the sky where the satellite is; if there is no satellite coverage at that moment, a countdown starts until one is overhead (Apple says this will typically be no more than fifteen minutes. The system needs a clear view of the sky to work properly, but Apple says that if there are obstructions, the system will will try to send anyway). At that point, the message, along with the user’s location, elevation, medical ID (if applicable), and device battery status are highly compressed and sent to the satellite, which then passes it along to the relay station. Unlike some satellite systems (see Huawei below), Apple’s Emergency SOS via satellite is fully bidirectional: when the message is received, emergency services can respond with further questions. If the user has set up emergency contacts, the complete transcript of the session will be sent to them automatically as well. Apple will enable a demo mode in November to give consumers a chance to see how the system works before they need it.

On the phone side, Emergency SOS via Satellite uses custom hardware and Apple-designed software stack. Some of the software runs on Qualcomm’s modem in the iPhone 14, but Apple would not disclose who makes the satellite-specific hardware components other than to confirm that it is not Qualcomm. Apple has been quietly funding cellular-satellite initiatives to the tune of $450 million, with most of that going to Globalstar. Globalstar has 24 second-generation satellites in a relatively high LEO 800 miles above the earth, with full regulatory approval in band 53 (1600 MHz for downlink, 2500 MHz for uplink) in most countries in the world. That means that an iPhone 14 purchased anywhere in the world should be able to use Emergency SOS via Satellite anywhere else in the world once relay centers are available in that area.

Apple is offering Emergency SOS via Satellite for free for two years. After that, monetization may be difficult. Is Apple really going to require an Apple One subscription for a rarely-used, but life-saving service? Apple could try to charge per use, but it would be expensive, and Apple should expect stories of people with $800 phones who refuse to pay for a satellite rescue. (People can be stupid.) Despite an investment of nearly half a billion dollars, plus satellite data costs, plus relay center rent, equipment, and 24x7 staffing, it may prove wisest to make Emergency SOS via Satellite an Apple ecosystem benefit.

T-Mobile Coverage Above & Beyond

Coverage Above & Beyond is technically fascinating and, like Apple’s Emergency SOS via Satellite, solves a literal pain point for people who get hurt outside the reach of cell sites. Unlike Apple, T-Mobile is aiming to provide full messaging access via SpaceX’s Starlink satellites, and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk even suggested that some voice or video may be possible in limited situations. That makes Coverage Above & Beyond more akin to a satellite phone, or at least a satellite messaging device, and also makes the communications network overall more robust by providing coverage when terrestrial service is down. Unlike dedicated satellite phones that require expensive dedicated devices, per byte charges, and monthly fees, T-Mobile’s system will use nearly any phone that supports T-Mobile’s network, iPhone or Android, at no charge, on most T-Mobile postpaid plans. However, the announcement is somewhat premature; regulatory approvals must be given, Starlink needs to launch new satellites to support the service, and it will be at least a year or more before it actually works.

In typical competitive fashion, T-Mobile CEO Mike Sievert launched Coverage Above & Beyond by positioning T-Mobile against its domestic rivals, saying, “the U.S. is big, 20% can’t be reached by cellular networks, and the wireless industry has no real plan to cover those areas. Until now.” T-Mobile is dedicating a small slice of its mid-band PCS spectrum to satellite communication, and SpaceX is fitting its next generation of Starlink satellites with larger antennas to be able to talk to them. T-Mobile owns this G block of the PCS spectrum (1910–1915 MHz for uplink and 1990–1995 MHz for downlink) across the U.S., and phones will simply think that they are connecting to a regular cell tower using T-Mobile spectrum, only one that is a bit farther away. This effectively puts a limited-capacity cellular tower (2 – 4 megabits per cell zone) in space. Musk claims that the service will work inside cars, purses, and pants pockets, though a clear view of the sky is strongly preferred.

T-Mobile plans to offer the service to consumers for free as part of its premium postpaid rate plans, which includes most of its subscribers. T-Mobile already offers free WiFi on some flights and free global roaming (with full 5G speeds in some places) to its postpaid subscribers as part of “Coverage Beyond,” and the intention is for Coverage Above & Beyond to be a natural extension. This is extra revenue for Starlink and should be a relatively affordable way for T-Mobile to add to its value proposition. T-Mobile will also offer reciprocal roaming for global carriers if they'll get on board. That could be challenging since those frequencies are used terrestrially in Europe and Asia. Still, if it is going to happen, T-Mobile parent Deutsche Telekom is a good bet for a first partner here.

Most T-Mobile compatible phones should work with the Starlink solution with no changes necessary, however, it will take a while before the service is up and running, and there are a lot of dependencies. SpaceX needs FCC approval to use its second generation satellites this way. To make launching the satellites economical, SpaceX needs to successfully complete design and deployment of the reusable Starship spacecraft and its super heavy booster rocket system, which have been under development for over a decade. SpaceX needs to successfully build the new satellites, and launch them. The system needs to be proven to work. If all goes well and there are no delays, service will start late next year in beta as the first satellites are launched, with full coverage in 2024 or whenever the full complement of satellites are in the sky. That’s a lot of “if’s,” and T-Mobile’s Sievert was clear that its announcement is just a technology agreement with SpaceX, not a formal product launch. However, the promise here is incredible: it solves coverage problems in areas that cannot be served terrestrially, will save lives when people need help and rescue, will keep people living away from the grid affordably connected, and provides a level of redundancy when the network on the ground goes down. Just about any T-Mobile phone can use it, and most of T-Mobile’s customer base will get access for free.

Everyone Else

T-Mobile and Apple aren’t the only carriers and smartphone vendors working with satellite providers, they are just the ones who have done the best job of explaining what they are doing.

Just days before Apple’s announcement, Huawei launched the Mate 50 Pro smartphone (priced around $1,000) with its own direct-to-satellite messaging system. The Mate 50 Pro connects to the BeiDou satellite constellation that are in stationary orbit over China, so the system is limited to that country. The Huawei system is also only able to send text and location data, not receive it, so users won’t know if their SOS was received by anyone. No pricing information on the service has been provided. Finally, like all Huawei phones, the Mate 50 line will be challenged by the lack of 5G thanks to its position on the U.S. Entity List. (Huawei lacks access to Google apps and services, too, but that is less of a concern for China-only phones). Without 5G, Huawei’s phone sales have dropped precipitously even inside China, and the Mate 50 Pro is unlikely to change that, but the satellite connectivity it offers does put some pressure on Apple to open relay centers in China quickly and expand Emergency SOS via Satellite in that market. Apple sells a lot of iPhones in China.

Lynk Global was the first company to send a text message from space to an unmodified Android phone back in 2020, the first step in its goal of putting a constellation of satellites up to provide coverage to phones outside the range of terrestrial cell towers. On September 16, it announced that the FCC granted Lynk, “the world's first-ever commercial license for a satellite-direct-to-standard-mobile-phone service,” with service slated to begin in late 2022. To provide “universal mobile broadband,” coverage, Lynk will need to launch thousands of small satellites, though it is starting much smaller. Lynk’s executives talk a lot about non-terrestrial networks helping during disasters and connecting portions of the world that don’t currently have service. However, this presumes that today’s least connected people – most of whom are poor – will be able to pay enough to support the system. In any case, carriers are interested; 30 have signed up to test the system and 15 have agreed to offer service as add-ons to their existing cellphone plans when it is operational. There is no word on cost. Lynk’s first commercial satellite went up in April, and three more satellites are due to go up later this year.

Verizon previously announced that it is working with Amazon's LEO satellite network, Project Kuiper. The idea is different than what Apple is doing with Globalstar or T-Mobile is planning with SpaceX: rather than your phone connecting to the satellite, Verizon will deploy lots of cell towers in areas where it couldn't before, using the satellite for backhaul. Some of the benefits are similar: you won't need a new phone, and rural coverage improves without needing a special pricey plan. It won't work deep in the desert or in the middle of Lake Michigan, but where it does work it shouldn't be limited to messaging, and Verizon is unlikely to charge consumers based on what method it uses to connect cell towers to the rest of its infrastructure.

Despite all of the above, AST SpaceMobile press releases still describes itself as, “the company building the first and only space-based cellular broadband network accessible directly by standard mobile phones.” Unlike T-Mobile and SpaceX, AST SpaceMobile intends to provide full broadband coverage using satellites. An initial BlueWalker 3 test satellite has been launched into orbit with FCC approval for cellular use, and five more satellites are planned. AST SpaceMobile has signed non-binding MOUs with AT&T in the U.S., Orange, Vodafone for Africa and Europe, Smartfren Telecom in Indonesia, Globe and Smart Communications in the Philippines. Japan’s Rakuten was also an early investor. Service is aimed to start in the 2023 – 2024 timeframe. Pricing targets have not been announced.

Cellular-satellite connectivity of one kind or another has been in the works for decades, and the 5G standard (3GPP Release 16) can incorporate it. Qualcomm already built n53 support – the frequency used by Globalstar’s existing satellite network – into the X65 modem found in many Android phones, including the last couple generations of Samsung Galaxy S smartphones. At IFA, Qualcomm added the word, “satellite,” to its keynote slide listing its modem capabilities. This is a great marketing move. As near as I can tell, this is technically accurate – if you build a Globalstar satellite phone around a chip that integrates it like a Snapdragon 8 Gen 1 SoC, it can talk to the satellite. However, a Galaxy S22 is not a satellite phone. One giveaway: Samsung makes many bold claims but has never even hinted that a Galaxy S22 can be used to talk to satellites. Another clue is that the Galaxy S22’s antennas are tiny lines on the outside of the case. These antennas are designed to talk to towers on the ground that are poorly disguised to look like trees; a satellite phone requires a large external antenna stub that is powerful enough to reach space. Qualcomm will certainly build support for all cellphone-to-satellite systems listed above going forward – if any of them prove commercially viable, MediaTek will undoubtedly follow, too. However, silicon doesn’t put satellites in the sky or convince consumers to pay extra for a universal coverage plan.

To discuss the implications of this report on your business, product, or investment strategies, contact Avi at avi@techsponential.com or +1 (201) 677-8284.

[published Sept 15, updated Sept 16 after Lynk Global announced a new FCC license]